I almost got away with the idea of not going to the Union Chapel. After they cancelled their summer run of Nunsense (a musical about nuns, inspired by a line of greeting cards, apparently), I was ready to scrub them off my list, but alas, when I gave their website one final check to make sure I hadn’t missed anything, I spotted a show I hadn’t seen before. They must have sneaked it in when I wasn’t looking. A Web in the Heart. On for only one day. Three performances. Immersive theatre. My favourite thing.

The web copy looks intense. Not just the blurb about the show. Under all that there are six whole paragraphs worth of content warnings and access info. Loud noises. Small rooms. Blacked out spaces. Enactments of racially motivated state violence.

With the promise of further content warnings during the performance.

So a nice cheery way to spend a Sunday afternoon then.

I get there early. Doors times for theatre shows at music venues always confuse me. Am I supposed to turn up at the time on the ticket or no? Turns out no. And I definitely shouldn’t turn up even earlier than that, like muggins over here has.

Thankfully there’s a small park right next to the chapel. A slip of greenery between the church and the road. And I go plonk myself on a bench and soak in my leather jacket.

From my spot I can just about see the main doors of the Union Chapel and I keep an eye on them, waiting as people gradually turn up. They sit on the steps, turning their faces up to the sun, and generally make a show of enjoying this hell inferno that we are currently living in.

When we reach three waiters, I walk over, and lean myself against one of the bollards in the shade. But I don’t get to stay there long, as someone has come out through a side door and is making an announcement. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he says. “If you’d like to come in here.”

Well, I for one would very much like to. So I follow him.

On the other side of the heavy wood door I find a narrow brick corridor. There’s a table set up in here as a makeshift box office.

“Are you on the list?” the box officer asks each of us in turn.

“I think I bought tickets for the later show,” someone ahead of me meekly admits.

“Oh, that’s fine,” says the box officer. “As long as you show up…”

That’s the attitude!

“Are you on the list?” she asks me when I reach the front of the queue.

“Hi, yes. The surname’s Smiles.”

She checks down her list, her pen tracing down the names. “Who did you book with?” she asks, her pen having reached the end of the page.

“Err, you? On your website.”

She looks again. “And was it for this time?”

I get out my phone and bring up the e-ticket. The time spot is blank. “It’s doesn’t say, but I definitely booked for 4.30. But it was at, like, 2pm, so maybe you’d already printed the lists?”

“Today?”

“Yes?”

“Okay,” she says, eyeing up the queue that’s been building up behind me. “I’ll check on the computer. How do you spell your surname?”

I spell it for her.

She nods. “You can go through,” she says, with a wave to the door at the end of the corridor.

I do, and it leads out into another corridor, where an usher is posted and waiting. “Just up the stairs to the bar,” she says.

Right then. Up the stairs, and into the bar. And blimey. Okay. This is… well, it’s less a bar and more of a barn. Impossibly high ceilings with wooden beams, red walls, and a massive stone fireplace.

I take a pew. Literally. Though it feels less like a thematic design choice and more of a make-use-and-mend method of furnishing the place. The other chairs on offer have more than a whiff of assisted living about them.

Gradually, the room fills up. More people turn up than I would have thought for a promenade performance about institutional racism on the sunny Sunday afternoon.

A couple of young woman take the table next to me.

“Is this a church?” one of them asks, suddenly looking around her.

“Yeah, it’s a chapel.”

“I’ve never seen a bar in a church before.”

“Oh, loads do. They’re all converting to become bars and community centres.”

“But they don’t still have services though!” she says, sounding scandalised by the very idea.

An usher comes round, hand delivering sheets of paper to the audience members.

“Programme for today,” she says, placing a freesheet on the table in front of me.

“Oh, thank you!” I do love a freesheet.

The usher moves onto my neighbours.

“Is that the stage?” one of them asks, pointing to a raised platform at one end. There’s a piano up there. And speakers.

“No,” the usher says. “It’s happening in the chapel. You’ll go through in about five minutes.”

And sure enough, five minutes later, there’s an announcement.

“Please head over to the chapel now. No alcohol is allowed in the chapel, so please finish your drinks in the bar.”

With that mixed messaging, we traipse back down the stairs the way we had come, and nip through a side door, into the chapel.

There’s someone playing piano.

And oh man… I’m not a religious person. And even if I was, I wouldn’t be Christian. But there’s something about seeing light filter through church windows that hits me right in the spiritual-zone.

As one, we all get out phones out and start aiming them upwards.

The ushers must be used to this reaction because they stand back, giving us time to take our fill of photos before gently guiding us into the first few rows of pews, where there are more pieces of paper waiting for us.

I take a seat and look what we’ve been given. It’s the words to I vow to thee my country. But different. Changed.

Oh god, I really hope they don’t make me sing. I’m not a singer. And, like, I’m a Jewish girl. Sort of. And in a church. And like, I’ve sung I vow to thee plenty of times. But that was at school. And I had to. And I hated every single enforced moment of it.

The cast come out. They sing. And then invite us to join in with them. Could I do it? Would I do it?

I compromised by standing up and mumbling along vaguely. Thankfully the cast are doing most of the work here. Good thing, as I vow to thee is a trickier hymn then most people remember, and with new words to fit into those convoluted rhythms, we needed all the help we can get.

The cast leave.

An usher comes up and starts counting.

“Right, this row,” she says, indicating the front row. “And you four,” she says, counting four people into the second row, with me as number two. “Please go through.”

“Do we leave these?” my neighbour asks, indicating the hymn seat.

“You can just put them in your seats.”

“But can I keep it?”

“Oh, yes. Keep it if you like!”

Excellent. Good on neighbour-lady for asking the important questions. I fold mine up and put it in my bag, hurrying to follow the others out though a low door and into a small foyer decked out in William Morris-esque wallpaper. From there, we move into a small room. Very small. Right. This is the room we were warned about.

We shuffle forward, but we’re bottle necking in the door, and the cast are already coming up behind us.

One of them gently pushes me aside so he can get in, and we all manage to shift and find room inside.

The two actors greet each other in delight, and then the lights go out.

Sound pounds around us. Shouting. A dog barking.

Someone near me gets out their phone and lights up the screen. Another phone appears on the other side.

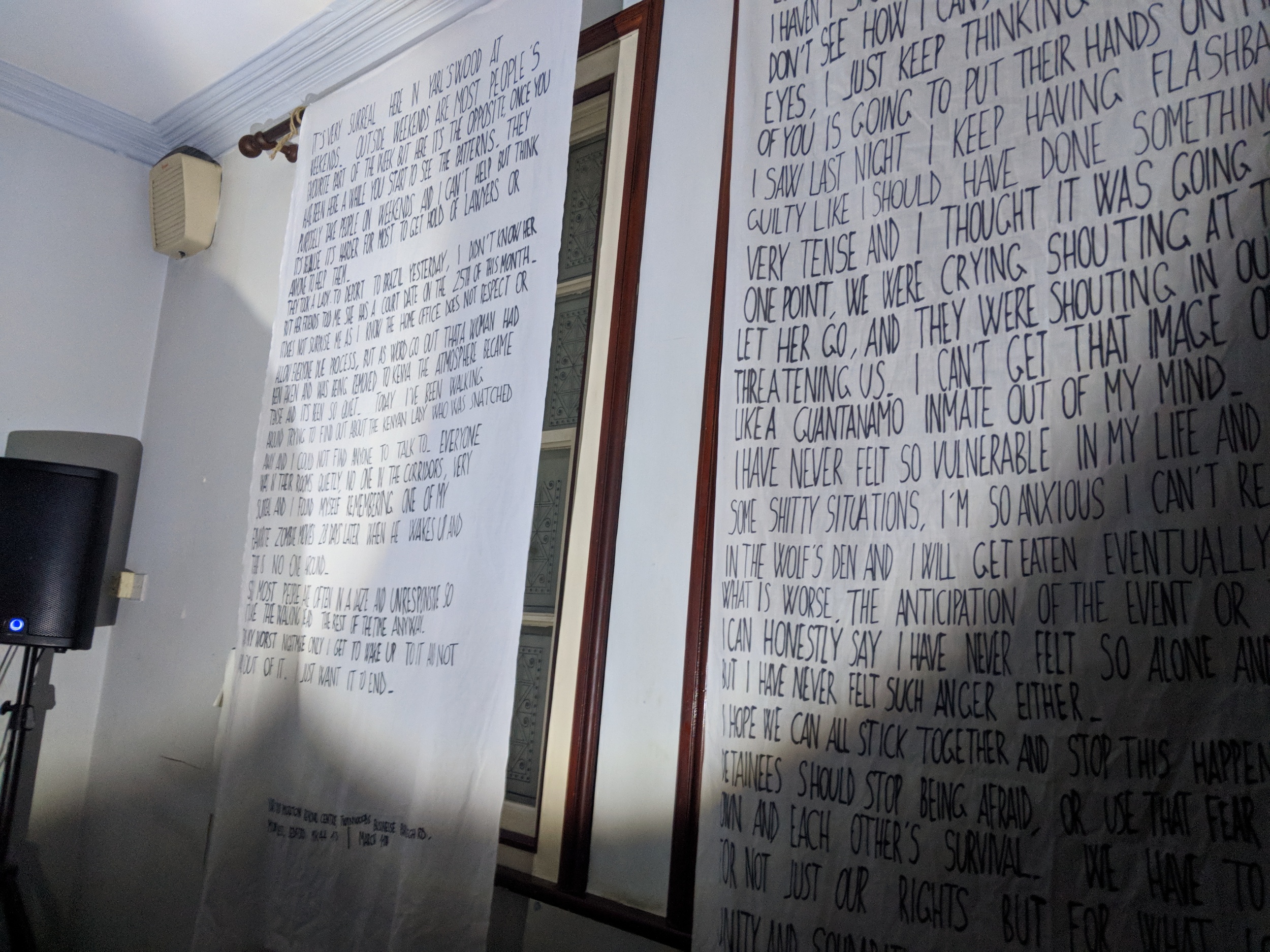

The actors switch on torches. They aim them at around the room. They’re showing us something. Words. Writ large in capital letters on banners overhanging the windows. Printed in tightly spaced lines on sheets of A4 stuck to the walls.

They hand the torches over to two audience members. And then they leave, shutting the door with a click behind them.

The torch-bearers stare at their newly acquired props for a moment, but then they realise what to do. They point them at the words. Lighting the way for us to read.

Stories of detention centres. Of cruelty. Of being kept in ignorance. Personal tales of anguish and pain.

“Is everyone ready to come to the next room?” asks the usher.

We nod. We are.

There isn’t far to go this time. Just down the corridor.

A grey room, filled with rows of seats.

Without being told, we all sit down.

An actor comes in. She introduces herself. She’s not here in character. She just wants to tell us something before the scene begins. There’s going to be racist language, she tells us. “You are very welcome to leave the room, and to come back. Feel free to use this room as you wish,” she says.

When she returns, she is in character. She’s a trainee officer in a detention centre. And so are we. She plays out a scene with her instructor.

We’re given small sheets of paper. What to do if you see someone being questioned by immigration. They want to teach us how to get around these meddling bystanders. An audience volunteer joins the actors to run through a scene.

At the end, we’re graduating. Fully fledged immigration officers. We’re told to take a hat out from under our chairs. There’s nothing there. The hats are imaginary.

We put them on.

The actor who greeted us returns. Not in character.

“You don’t have to spend the rest of the performance as officers,” she assures us. “Take the hats off.”

We do.

“Just remember,” she adds. “You’ve taken your hats off now, but I haven’t.”

We’re going back up the stairs now.

An actor calls us over to the bar.

“Free Ribena!” she says, handing out glasses of the stuff. “This is a Ribena bar! Come close. Take a drink. I want to ask a favour of you…”

There are three people in the bar. Each sitting at their own tables. We’re to join them. Talk to them. Cheer them up, if we can.

I go over to a young woman weeping into her wine glass. “Mind if I join you?” I ask.

She apologises for her tears. And then she tells her story. She’s a teacher. Her pupil is starving. He can’t claim free school meals. What can she do?

I don’t have the answers.

The next table is a woman writing. A page filled with the word ARAB, over and over again. She’s raging about the laws being pushed through, about NHS staff having to report on the nationalities of their patients, about immigrants having to pay more than the treatment actually costs.

“There’s a campaign,” she says. “Docs not Cops. If you just search that…”

“Docs not Cops?” I repeat.

She nods. “There’s also a hashtag. #PatientsNotPassports,” she says with a small smile of humour at the phrase.

There’s only two other people at the next table. A young woman, and our actor. He’s a landlord. He just chucked out his tenants, because one of them didn’t have the immigration paperwork.

He doesn’t sound very remorseful about the whole thing.

“What would you do?” he asks us.

“I’d turn a blind eye,” says my fellow audience member.

I shrug. I wouldn’t be a landlord. That’s what.

I did not like him.

“I didn’t feel sorry for the landlord at all,” says the young woman as we leave for our next destination.

“I gave him a really hard time,” pipes up another audience member.

“Property-owning capitalist pig,” I inject.

We really didn’t like him.

We’re going back down to the chapel. We retake our seats in the pews. We’re going to do some Theatre of the Oppressed. I’ve never done Theatre of the Oppressed. I’ve never wanted to.

Cardboard Citizens used to bring their Theatre of the Oppressed shows to Canada Water Culture Space back when I worked there. I always felt that I should go. Just to see what it was all about. But then I’d read a description of how it all works, and I would very firmly pick up my coat at the end of the day, and make sure I was safely at home by the time it kicked off.

If you don’t know what it is, I suggest reading their website, but basically, the actors run a scene, the audience yells stop at a turning point in the story, and then the help to reshape what happens. Changing the scene to form a better outcome.

Our MC for the show steps up and explains this.

They run through the scene.

We all shout STOP.

“Right at the beginning!” says our MC. “So you know how to help things. But why didn’t our character?”

Audience members starts shouting out answers.

“Fear.”

“She feels powerless.”

“Indifference!

“And how would you show that?” the MC asks.

He jumps onto the stage. “I want you to come up here, and move the actors into position. They’ve given permission for us to touch them, but it’s nice to ask. It’s polite.” He turns to one of the actors. “May I touch you?” The actor nods. “You can pose them,” says the MC, pushing down one of the actor’s shoulders so that he's lopsided. “And you can show them. But you cannot describe what you want them to do.”

Three volunteers from the audience go up, and after asking nicely, mould their actors into the appropriate positions to convey the emotions.

“And can you help?” asks the MC. “How do we conquer these emotions?”

More people go up. They talk to the actors. Give advice.

One woman explains to the actor representing fear, that she must fake it till she makes it.

One man reads the pamphlet we were given earlier to the powerless actor, giving him the tools he needs.

The scene runs again. This time with an audience member in place of an actor. She steps in. Stopping the detention officers. Informing their target of his rights.

We all applaud.

She did very well.

And then it’s time to go. But not before we are reminded that we have to do our things our own way. That we must do what we are capable of. In whatever way we can.

Just like being an audience member, I suppose. Each of us taking part as much as we are able. Drink the Ribena, chat to the actors, but draw the line at going up on stage? That’s fine. We all have our limits.

Knowledge is power, and content warnings mean you can be prepared.

“The bar is still open, if you like,” says an usher.

I wouldn’t mind. But I have somewhere else to be.

Somewhere where the name is it’s own content warning.

I’m going to Magic Mike Live…